Working at a brick-and-mortar business as a tech bro

In my ~2 month stay in America, I’ve stumbled upon a volunteer unpaid job as a PM (I guess?) helping my mother and brother run two restaurants.

ContextPermalink

Day in the LifePermalink

RevelationsPermalink

Just do itPermalink

My perfectionist self often dislikes doing things that I don’t think that I can do well. As a result, I often have a hesitation to start things that I’m not already “good at”, which counterproductively means that I don’t ever want to do anything at all (even for the things that I am “good at”, I can always find someone better than me and thus talk myself out of it).

This is a constant struggle that I’ve had to intentionally fight. Whether it be forcing myself to be a TA so that I could get over my social anxiety, doing public speaking to prove to myself that stuttering wasn’t actually an impediment, or doing a math degree just to prove to myself that I could, I’ve often found ways to combat this. However, the feeling of fear and hesitation never goes away; I just accumulate undeniable rational evidence to myself to prove that those feelings are incorrect.

During my work here, I can consistently point to things that I’m not “trained” to do. For example, how do I know what ways a restaurant can make money? How do I know how the operations of a restaurant work? How does accounting work?

There are so many things that are a nature of the work that I have 0 experience in doing which require me to overcome my perfectionist urge. I have a tendency to shy away from the impactful work and instead just do the tasks that I think I either enjoy or am “good at”. But then I think about how my mother, who came to America as an immigrant escaping poverty in the Philippines, could somehow do just enough of it to survive, and me, a Yale graduate, somehow can’t, and I think “OK, I should be able to do it after all.”

How can I expect to be good at something if I’ve never done it before? And isn’t it better to do something poorly, learn how to do it better, and then do it correctly over time, than to never do it at all? Instead of trying to plan the perfect way to do something, why don’t I just start and then learn how to do it as I go?

Practical tip: If you’re not sure what to do, simplify the problem until you can find something you can do to make progressPermalink

If you can’t solve something, figure out a simpler version of the question that you can solve. I find myself hesitating to start answering questions because I feel like I don’t have a clear roadmap for how to answer the question. For example, a request as simple as “do the accounting” seems daunting to me at first because I don’t know all the possible sources of income or the possible sources of costs. I also don’t know anything about accounting. I also have incomplete information and don’t even know how to ask for data that I don’t know exists. At the start, the ambiguity of this question made me hesitant to even start it, since I felt paralyzed by not even knowing where to start.

But, when I sat down to think about it, I simplified the question into steps that, even if they weren’t perfect, would at least give me a start. So, to start, I decided that I would start with answering the question “are we making money?”. This is the most important question to actually answer, at the end of the day. Plus, framing it in this way lets us break down the task into two sub-questions:

-

How much money do we make? Luckily figuring out the number of sales is a simple matter of looking at the POS (point-of-sale) software used, since all sales have to go through that. So, determining the inbound sales was as straightforward as organizing this information in the POS and then exporting it to a useful format.

-

How much money do we spend? This question would be simple to answer if there were a single, well-organized ground truth source for it. But, instead, I have at my disposal a folder of receipts and invoices, lots of vendors sending angry emails about unpaid debts, and costs that are paid over the phone that you only learn about after the fact.

I accepted that I couldn’t tackle every single source all at once, nor could I be 100% correct. But, at the very least, I could simplify the problem and try to tackle the largest factors first. I can figure out what the largest costs are, why those are the largest costs, investigate those, and then go from there. By prioritizing learning about the largest expenses and then updating my priors with that information, I could build a mental framework where I could estimate what costs should be, to a reasonable margin of error, and do all calculations with that.

Sounds pretty simple, and this gets 90% of the way there. By focusing on the overarching question “are we making money?” and answering the most obvious possible questions, “how much money do we make?” and “how much money do we spend?”, the task becomes so simplified that it makes it easier to organize all the information and deliver something useful to the business.

There are still other interesting and useful questions that could and should be answered, but starting with a simpler version of a question and then simplifying the task as much as possible really helped me get over my perfectionist paralysis.

Don’t “just do it”. Think about what you’re doingPermalink

Everything costs money, and everything costs more money when you’re a businessPermalink

A constant complaint that my mother has when talking about the business is about how much it costs to run a restaurant. Once I personally started sorting out the finances, I can see why.

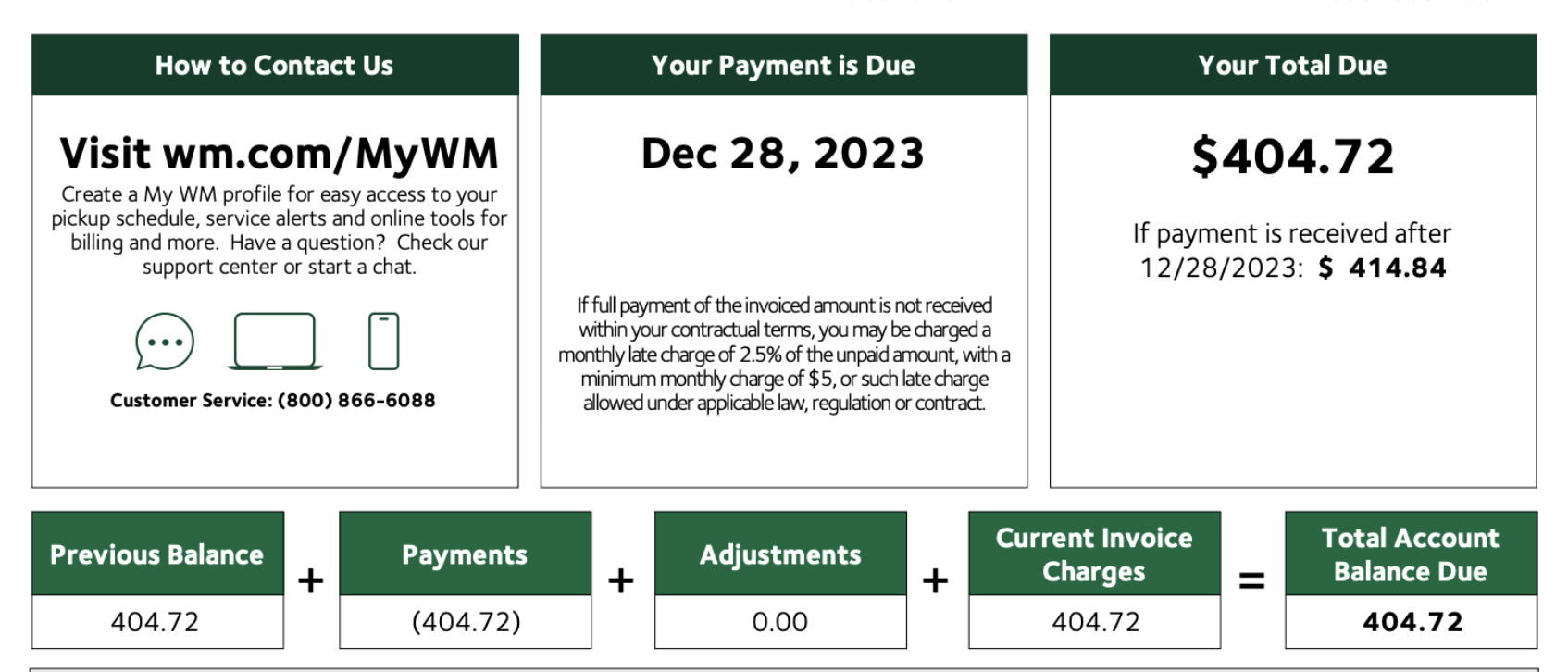

Fun fact: it may cost your local restaurant $400 per month just to get their trash taken out. Don’t believe me? Here’s a receipt:

$400? I’ll do it for free, just give me a truck and I’ll drive the trash to the local landfill myself.

I can see why businesses can thrive on providing such niche services as supplying towels or doing laundry. I was shocked by how easily the costs racked up. An individual person may rack up small purchases in the $5 - $20 range that they don’t notice, but for a business, these small purchases can instead be $100 - $500 (or more, of course, as a business grows larger).

Payroll also becomes a date to circle every two weeks. As payroll approaches, I need to double-check the bank account and verify that there indeed is enough to cover all of payroll. I now see why both employees and business owners know what day is payroll, but for vastly different reasons.

Problems are solved with more salesPermalink

Rent is too high? Just have more sales. Not enough servers want to join since their tips are too low? Just have more sales. Having to be more stringent about food inventory to reduce food costs? Just have more sales. Unable to afford more workers, even if their work is essential? Just have more sales.

As obvious as it sounds, so many problems can be solved just by having more sales. Profit is affected by both inbound sales and outbound costs, and although in a time of leanness one can cut costs, costs can only be cut to a certain degree, and it will often come with large effort and with a sacrifice to be made in quality. However, costs are less of a problem if one ruthlessly focuses on sales instead. Easier said than done, of course, but it was a revelation to learn just how many everyday problems can be most easily solved with just having more sales.