Experiments with LLM classification for political content (Part IV)

Using LLMs to classify if social media posts are political or not (Part IV).Permalink

I’m working on a project that involves gathering social media posts from Bluesky and analyzing them. Part of that project requires knowing which posts are about political or social topics, and if so, what political side they support. Current ML classifiers don’t work that well out of the box, so I’m trying to create our own classification scheme using LLMs. I’m trying to use LLMs in order to classify Bluesky posts as either having political content or not, and if so, the political ideology, and I’ve found that LLMs work quite well for this task. I’ve used Llama3-8b and Llama3-70b via Groq so far, but are also open to experimenting with other open-source models as well (I have the on-prem infrastructure to host our own models, which is much cheaper at scale).

Previously, I’ve tried using just naive text classification and then afterwards adding context to the classifications. Now that I’ve shown that individual prompts work, I’ve also worked on how to include batching and adding some (simple) scaling for the prompts. I then added a service for getting current news coverage from different news orgs across the political spectrum and created an interface for surfacing relevant articles given a query.

Currently, I’m working on figuring out what data we want for annotation and inference as well as gathering said data.

Defining our annotation taskPermalink

Our goal is to figure out which Bluesky posts are political or not. Most out-of-the-box classifiers end up being pretty bad at this task. LLMs though, since they encode a fuzzy summary of human knowledge (at least, knowledge on the Internet), does pretty well at this task. We want to be able to definitively show this though, which requires collecting annotated training data for us to test our classifiers against. Before annotating the data, we need to define some constraints for what data to collect, especially since we can collect all posts available on Bluesky (due to them open-sourcing their firehose).

Our end goal is to create social media feeds that are (at least, to a first approximation), representative of what a normal social media feed would look like. But, having a firehose means that we have access to millions of possible posts to use for the feeds. So, for annotation, we want to get posts that are representative of the types of posts that we’d want to put in our eventual feeds anyways. Here’s some criteria that I think are going to be useful for determining what those posts are:

- Posts that are more recent: on Facebook and Twitter, most of the posts that we get come from the last few days. Although Bluesky doesn’t have nearly the same degree of activity as these other platforms, if we can keep the posts recent, that would be ideal. I arbitrarily set a limit of <=7 days for the posts as a recency filter.

- Posts that are most likely to get engagement: social media algorithms naturally surface posts that will be the most engaging for us. For us to mimic social media feeds, we want to get posts that are most engaging. However, Bluesky doesn’t have a default engagement algorithm like Facebook or Twitter. The default feed on Bluesky is a follow feed, consisting of posts from people that the user follows. As a result, the users that have the most followers will get, on average, the most engagement. If we look at the most liked posts per week, we see a general trend that confirms this, where the posts that get the most likes are the ones from users that have the largest followings. We could build engagement-maximizing feeds (and there have been attempts at this, such as this feed, this feed, and this feed), but they’ll be highly correlated to the posts that get the most likes. Since posts that get the most likes are highly correlated to the users with the largest followings (much more so than other social media platforms), the posts that will generally be the most engaging will be the ones that are most liked.

Therefore, we’ll pull posts that are the most liked and most recent and annotate those.

Describing the data that we’ll collect for annotationPermalink

Estimating post countPermalink

If we look at the SQL queries that power these feeds, we notice two things:

- The posts are sorted by the number of likes

- Each feed has a maximum of 1,000 posts.

This means that between the “Catch Up” and “Week Peak” feeds, we’d get a maximum of 2,000 posts. There’s likely some overlap, but this is offset by the fact that the posts in the “Week Peak” feeds have had more time to accumulate likes. Let’s conservatively estimate (until we get more accurate numbers later) something on the order of ~1,800 posts in one batch of collection between the 2 feeds. Over the course of the week, most of the new sources of posts will likely come from the “Catch Up” feed, as the posts that are added to the “Week Peak” feed each day are likely to be posts that were in the “Catch Up” feed the day before.

Let’s assume that there’s an even distribution of posts in the “Week Peak” feed across the past 7 days. In that case, let’s say that 150 of the posts come from the past 24 hours. These posts would also necessarily be in the “Catch Up” feed as well. We can reasonably assume that the posts that are in the “Week Peak”, to a first approximation, were also all in their respective day’s “Catch Up” feed. As a result, the only major source of new posts would be the “Catch Up” feed, which would give us 1,000 new posts a day maximum.

There are a lack of conservative posts on BlueskyPermalink

We want to find political content on Bluesky, but unlike Twitter, which has a variety of political content across the entire political spectrum, Bluesky leans very liberal and left-leaning. This is a concern for our project since we want to present both Democract and Republican content to users (instead of just whatever agrees with their political affiliation, which is what most algorithms would surface). Our algorithm will have a minimum of 25% outgroup content and a maximum of 75% ingroup content. This means that for users that identify as Democrat, for every 100 political posts, we want to show at least 25 Republican posts. For users that identify as Republican, we want a maximum of 75 Republican posts (but a minimum of 50, so that we don’t overwhelm users with outgroup content, which has been shown to be perceived as threatening to people).

If we want to provide 160 posts per person per day, and 50% of those are political, then that is 80 posts that are political. For a Democrat, we would have to provide at least 20 (25%) conservative posts. Prior initial testing with our classifier estimated that in ~300 posts pulled from the “Week Peak” feed, ~2% (7) posts were classified as right-leaning. Let’s say that we’re OK using conservative posts from the past week, but we’d like to use new posts every day (so, for example, if a lot of conservative posts were written in a given day, we’re OK showing a sample of it today and the rest tomorrow). Let’s overestimate and say that we want 30 conservative posts per day for Democrats. At a 2% hit rate, we would need 1,500 total political posts (or 3,000 total posts, if we assume a 1:1 political:non-political ratio, as per our pilot) in order to comfortably get 30 conservative posts. For Republicans, let’s say that we want 70 conservative posts per day, that number goes up to 3,500 political posts (or 7,000 total posts).

If we just look at the “Week Peak” and “Catch Up” feeds, we get a maximum of 2,000 posts. Therefore, just looking at the posts from the most liked feeds doesn’t give us enough conservative content. There are a few ways that we can try to circumvent this limitation.

Method 1: Follow conservative accounts on BlueskyPermalink

I found a few conservative accounts in ~1 hr. of searching, but there aren’t that many:

- https://bsky.app/profile/rpsagainsttrump.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/patriottakes.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/pointmannews.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/newsmax.com

- https://bsky.app/profile/fox-news.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/endwokeness.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/conservativehippie.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/mjgranger1.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/hollyhock17.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/robrx.bsky.social

- https://bsky.app/profile/itaintthatserious.bsky.social

We can see through this clustering algorithm visualization that these conservative accounts occur in a similar cluster. There also aren’t that many accounts in the first place (Bluesky leans very liberal). If we end up not having enough conservative posts for our project per day, we may have to bootstrap it artificially with posts from accounts such as these. If we look at the activity of these accounts, we see that they post frequently enough to hit our requisite thresholds.

However, relying on these accounts for content creates a weak point, as at any given time these accounts could change their posting behavior (or stop using Bluesky altogether). In fact, many accounts on Bluesky have this problem - there was a influx of users when the app first went viral, as it became an alternative to Twitter, but many people tried it once or twice but never used it again afterwards. There are a few accounts belonging to conservatives, such as this, this, and this, which are inactive.

Method 2: Bootstrapping using bot accountsPermalink

If our problem is a lack of conservative content, another approach that we can consider is bootstrapping conservative content artificially using bot accounts. This is already done on Bluesky, such as with this bot account, which just retweets Fox News articles. We want to display true content from Republicans, not just news content, so we would want to find representative Republican content and repost that with our bot.

Possible data sourcesPermalink

- Reddit: We can get posts from conservative subreddits (though we would need to decide how to pick the posts to gather in the first place).

- Twitter: Twitter is the ideal data source for us to use, as it has the most political content. However, there are a few things to consider:

- Accessing the API is quite costly: The Twitter API now costs $100/month. The free tier only supports creating posts on Twitter, not pulling data from Twitter. For us to use the API requires paying $100/month for access. Plus, the API limits are quite low and we can only have one app use it. Unfortunately, unlike in the past, Twitter also doesn’t have a tier for academics.

- Alternative access methods such as web-scraping are illegal: If we want to publish our results, we want to make sure to comply with any usage requirements. As a result, we can’t use something like web-scraping in order to get the data that we actually need.

- Facebook: It looks like it could be possible to get post content using Facebook’s Graph API, through an endpoint such as this. Still needs to be explored, but it is something to consider.

General considerations across data sources

- We need to pick which data to use in the first place: We want content representative of moderate users who are normally muted on social media. We need to create a strategy that faithfully and reliably gives us that content.

- We only know the opinions of the people who post in the first place, which is self-selecting: This is a general limitation with using social media data, since most people who use social media don’t post. For example, 25% of Twitter uses produce 97% of messages and 25% of TikTok users produce 98% of videos. We can’t circumvent this limitation, but it is something that we need to keep in mind, especially if we operate off the hypothesis that moderate opinions are generally muted.

How do we pick which posts to usePermalink

Even if we have data to pool from, we want to be able to select which ones to use. The high-level problem that we’re trying to solve is how to mitigate social media selectively upranking the most extreme versions of opinions. We want to uprank more moderate and nuanced opinions across the aisle, as these are underrepresented in social media content. A common problem in social media is that each political side is represented as a monolith of quips and extreme opinions, and this is due to that type of outrage-inducing content being preferentially engaged with and thus upranked.

Our proposed approach is to downrank posts that are toxic (since the most extreme opinions generally are personal attacks, target outgroups, and display other toxic behavior) and uprank posts that are constructive (since we want to preferentially promote nuanced, thought-out opinions that promote dialogue). We apply this scoring algorithm on the Bluesky posts to determine which posts we want to preferentially show in our eventual recommendation algorithm. We can actually apply this same sort of logic on the posts from whatever data sources that we use. We can preemptively filter for non-toxic, constructive content out of the content in our data sources and then use that filtered pool of content in our project.

Pros and cons of bootstrappingPermalink

Pros

- We solve our content-related problems: We would have enough content to work with if we bootstrap other sources. We would also be able to be more selective about what content we want to use for our study if we have more options available to us.

- We bootstrap with real, not artificial, content: We bootstrap our approach using content posted by real online users. This makes the content organic and ecologically valid, as opposed to, for example, prompting an LLM to post the content.

Cons

-

The lack of conservative community is a limitation (though intractable and true regardless of our approach) Even if we pull conservative content, we can’t artificially stimulate people responding to those posts. We can’t convince conservatives to respond to those posts unless we tell our study users to comment on conservative posts, since there are no conservatives on Bluesky. We could artificially create community on our own with more bot accounts, perhaps spoofed using LLMs, but this doesn’t really faithfully represent what a conservative user would’ve prompted (plus it would require us creating very specific user profiles in order to steer the model away from generic, stereotyped responses). Using bots to post political content is not a new approach, but this has always been done in Twitter, where even bot content would get some engagement. It remains to be seen how much of a limitation the lack of community is.

-

Is the content that we get representative of what data we would’ve seen on Bluesky if there were a conservative community? For example, the argument could be made that the type of posts on Reddit is qualitatively different than the conservative content on a platform like Bluesky or another similar platform like Twitter. The more that the data source is like Bluesky, the better the approximation holds. But, one can argue that, for example, since people can write longer posts on a platform like Reddit, that somehow this makes the content qualitatively different.

We could test this empirically by taking liberal content on Bluesky and comparing it to similar liberal content from our data sources. We could see if they are likely to come from the same distribution empirically, either through quantitative tests such as testing the average sentiment or other values in either distribution or just by asking people if they can tell the difference between posts pulled from both sources.

Next stepsPermalink

In the immediate future, while figuring out the pros and cons of these approaches, I can just gather data from the most liked feeds as well as from conservative accounts and annotate those. At a minimum, we’ll want to annotate those posts in the first place.

Collecting the data to be annotatedPermalink

I’ll collect posts from the most liked feeds as well as the list of conservative profiles in order to create a preliminary dataset. I’ll address how to get other conservative data later on, but for now I’ll just collect the data that needs to be annotated.

I’ll collect data from two Bluesky feeds, the Daily Catch-Up Feed and the Week Peak Feed, consisting of the posts with the most likes in a given day/week respectively.

Let’s do some setup:

feed_to_info_map = {

"today": {

"description": "Most popular posts from the last 24 hours",

"url": "https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:tenurhgjptubkk5zf5qhi3og/feed/catch-up"

},

"week": {

"description": "Most popular posts from the last 7 days",

"url": "https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:tenurhgjptubkk5zf5qhi3og/feed/catch-up-weekly"

}

}

current_directory = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(__file__))

current_datetime_str = current_datetime.strftime("%Y-%m-%d-%H:%M:%S")

sync_dir = "syncs"

sync_fp = os.path.join(current_directory, sync_dir, f"most_liked_posts_{current_datetime_str}.jsonl")

The endpoint that we care about is defined in the client.app.bsky.feed.get_feed function, whose expected params are defined here.

We want to wrap this in a function that lets us send requests with appropriate pagination:

def send_request_with_pagination(

func: Callable,

kwargs: dict,

response_key: str,

args: Optional[tuple] = (),

limit: Optional[int] = None,

update_params_directly: bool = False,

silence_logs: bool = False

) -> list:

"""Implement a request with pagination.

Useful for endpoints that return a cursor and a list of results.

Based on https://github.com/MarshalX/atproto/blob/main/examples/advanced_usage/handle_cursor_pagination.py

""" # noqa

cursor = None

total_fetched: int = 0

total_results = []

if limit is None:

limit = DEFAULT_MAX_TOTAL_RESULTS_LIMIT

total_to_fetch: int = limit

if (

limit > MAX_POSTS_PER_REQUEST

and limit != DEFAULT_MAX_TOTAL_RESULTS_LIMIT

and not silence_logs

):

print(

f"Limit of {limit} exceeds the maximum of {MAX_POSTS_PER_REQUEST}."

)

print(f"Will batch requests in chunks of {MAX_POSTS_PER_REQUEST}.")

request_limit = min(limit, MAX_POSTS_PER_REQUEST)

while True:

if not silence_logs:

print(f"Fetching {request_limit} results, out of total max of {limit}...") # noqa

if update_params_directly:

kwargs["params"].update({"cursor": cursor, "limit": request_limit})

else:

kwargs.update({"cursor": cursor, "limit": request_limit})

res = func(*args, **kwargs)

results: list = getattr(res, response_key)

assert isinstance(results, list)

num_fetched = len(results)

total_fetched += num_fetched

total_results.extend(results[:total_to_fetch])

total_to_fetch -= num_fetched

if not res.cursor:

break

if total_fetched >= limit:

print(f"Total fetched results: {total_fetched}")

break

cursor = res.cursor

return total_results

Using this, our function becomes straightforward. We set our “limit” to None so we get all the posts from the feeds.

def get_posts_from_custom_feed(

feed_uri: str,

limit: Optional[int] = None,

cursor: Optional[str] = None

) -> list[FeedViewPost]:

"""Given the URI of a post, get the posts from the feed."""

kwargs = {"feed": feed_uri}

res: list[FeedViewPost] = send_request_with_pagination(

func=client.app.bsky.feed.get_feed,

kwargs={"params": kwargs},

response_key="feed",

limit=limit,

update_params_directly=True

)

return res

When we grab the post, we also want to add a few other fields that will help us know when we synced the posts as well as at what URL the post can be found:

def create_new_feedview_post_fields(

post: FeedViewPost, source_feed: Literal["today", "week"]

) -> dict:

res = {}

handle = post.post.author.handle

uri = post.post.uri.split("/")[-1]

res["url"] = f"https://bsky.app/profile/{handle}/post/{uri}"

metadata: dict = {

"source_feed": source_feed, "synctimestamp": current_datetime_str

}

res["metadata"] = metadata

return res

def process_feedview_posts(

posts: list[FeedViewPost], source_feed: Literal["today", "week"]

) -> list[dict]:

return [

{

**post.dict(),

**create_new_feedview_post_fields(

post=post, source_feed=source_feed

)

}

for post in posts

]

Now we can put it all together:

def get_latest_most_liked_posts() -> list[dict]:

"""Get the latest batch of most liked posts."""

res: list[dict] = []

for feed in ["today", "week"]:

feed_url = feed_to_info_map[feed]["url"]

print(f"Getting most liked posts from {feed} feed with URL={feed_url}")

posts: list[FeedViewPost] = get_posts_from_custom_feed_url(

feed_url=feed_url, limit=None

)

processed_posts: list[dict] = process_feedview_posts(

posts=posts, source_feed=feed

)

res.extend(processed_posts)

print(f"Finished processing {len(posts)} posts from {feed} feed")

return res

def export_posts(posts: list[dict]) -> None:

"""Export the posts to a file."""

with open(sync_fp, "w") as f:

for post in posts:

post_json = json.dumps(post)

f.write(post_json + "\n")

num_posts = len(posts)

print(f"Wrote {num_posts} posts to {sync_fp}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

posts: list[dict] = get_latest_most_liked_posts()

export_posts(posts)

If we look at the output we can see that we successfully synced the posts:

>>> python helper.py

Finished processing 995 posts from today feed

Finished processing 986 posts from week feed

Wrote 1981 posts to /Users/mark/Documents/work/bluesky-research/services/sync/most_liked_posts/syncs/most_liked_posts_2024-05-07-12:19:13.jsonl

Storing data into MongoDBPermalink

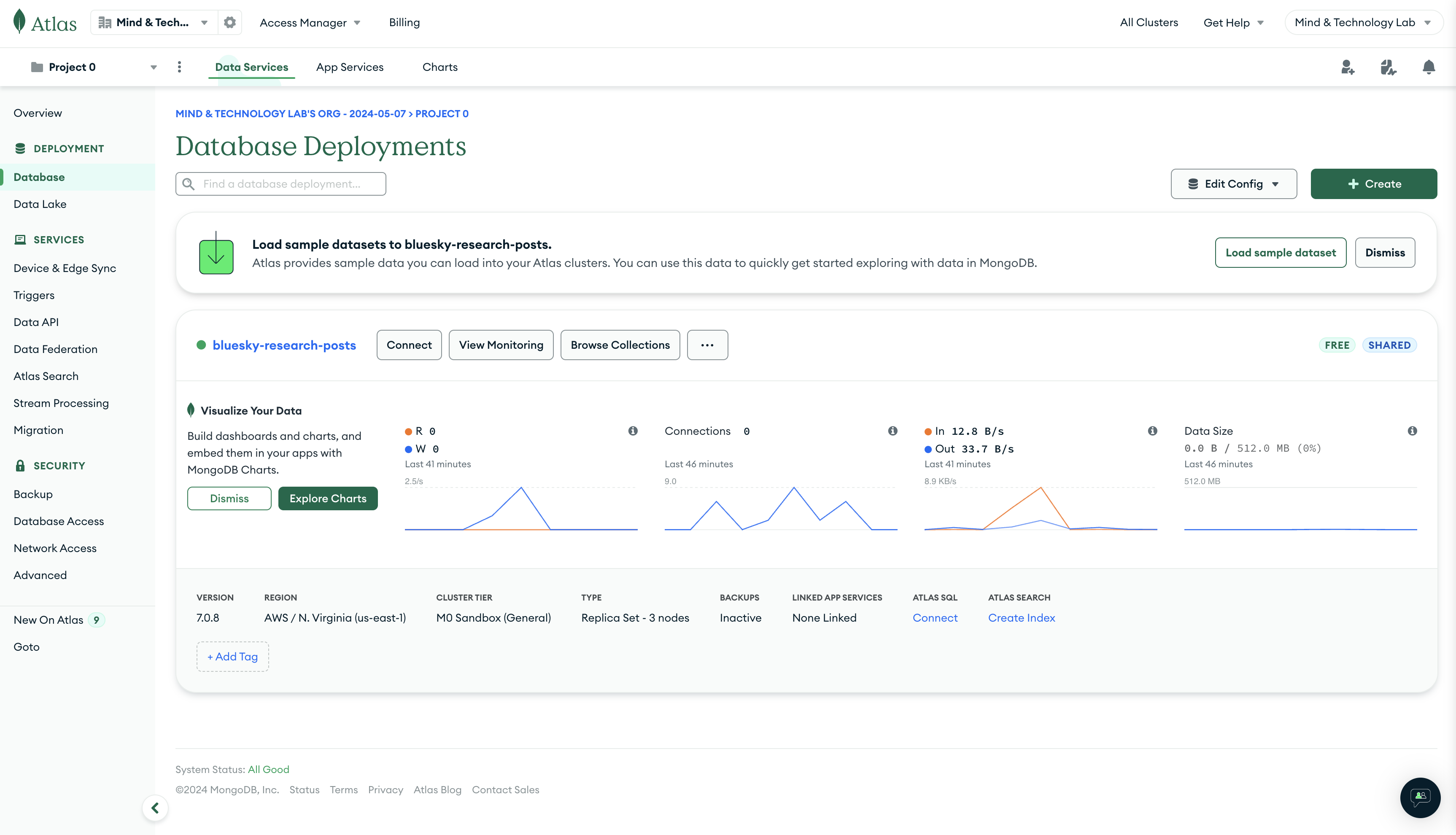

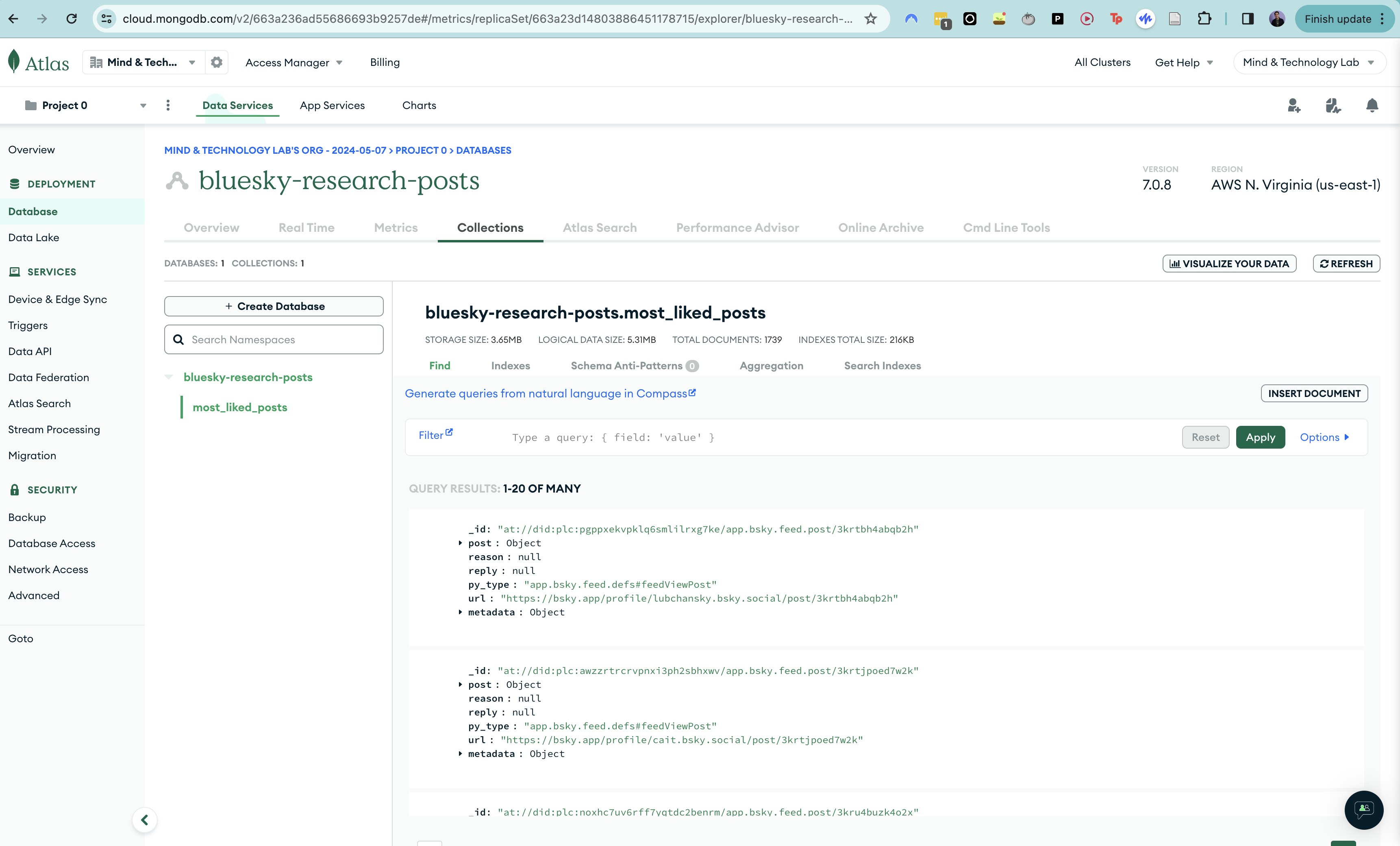

Let’s store our data into MongoDB. This’ll give us a NoSQL store to store our data as JSONs.

We first need to start by creating a MongoDB account. Then, we’ll create a database, called “bluesky_research_posts”:

We’ll now set up the connection to MongoDB in Python:

mongodb_uri = MONGODB_URI

mongo_db_name = "bluesky-research-posts"

mongo_collection_name = "most_liked_posts"

mongodb_client = MongoClient(mongodb_uri)

mongo_db = mongodb_client[mongo_db_name]

mongo_collection = mongo_db[mongo_collection_name]

We can now write the posts directly to MongoDB. We want the URI to be the primary key

def insert_chunks(operations, chunk_size=100):

"""Insert collections into MongoDB in chunks."""

total_successful_inserts = 0

duplicate_key_count = 0

for i in range(0, len(operations), chunk_size):

chunk = operations[i:i + chunk_size]

try:

result = mongo_collection.bulk_write(chunk, ordered=False)

total_successful_inserts += result.inserted_count

except BulkWriteError as bwe:

total_successful_inserts += bwe.details['nInserted']

duplicate_key_count += len(bwe.details['writeErrors'])

return total_successful_inserts, duplicate_key_count

def export_posts(

posts: list[dict],

store_local: bool = True,

store_remote: bool = True,

bulk_write_remote: bool = True,

bulk_chunk_size: int = 100

) -> None:

"""Export the posts to a file, either locally as a JSON or remote in a

MongoDB collection."""

if store_local:

print(f"Writing {len(posts)} posts to {sync_fp}")

with open(sync_fp, "w") as f:

for post in posts:

post_json = json.dumps(post)

f.write(post_json + "\n")

num_posts = len(posts)

print(f"Wrote {num_posts} posts locally to {sync_fp}")

if store_remote:

duplicate_key_count = 0

total_successful_inserts = 0

total_posts = len(posts)

print(f"Inserting {total_posts} posts to MongoDB collection {mongo_collection_name}") # noqa

formatted_posts_mongodb = [

{"_id": post["post"]["uri"], **post}

for post in posts

]

if bulk_write_remote:

print("Inserting into MongoDB in bulk...")

mongodb_operations = [

InsertOne(post) for post in formatted_posts_mongodb

]

total_successful_inserts, total_successful_inserts = insert_chunks(

operations=mongodb_operations, chunk_size=bulk_chunk_size

)

print("Finished bulk inserting into MongoDB.")

else:

for idx, post in enumerate(posts):

if idx % 100 == 0:

print(f"Inserted {idx}/{total_posts} posts")

try:

post_uri = post["post"]["uri"]

# set the URI as the primary key.

# NOTE: if this doesn't work, check if the IP address has

# permission to access the database.

mongo_collection.insert_one(

{"_id": post_uri, **post},

)

total_successful_inserts += 1

except DuplicateKeyError:

duplicate_key_count += 1

if duplicate_key_count > 0:

print(f"Skipped {duplicate_key_count} duplicate posts")

print(f"Inserted {total_successful_inserts} posts to remote MongoDB collection {mongo_collection_name}") # noqa

def dump_most_recent_local_sync_to_remote() -> None:

"""Dump the most recent local sync to the remote MongoDB collection."""

sync_files = os.listdir(os.path.join(current_directory, sync_dir))

most_recent_filename = sorted(sync_files)[-1]

sync_fp = os.path.join(current_directory, sync_dir, most_recent_filename)

print(f"Reading most recent sync file {sync_fp}")

with open(sync_fp, "r") as f:

posts: list[dict] = [json.loads(line) for line in f]

export_posts(posts=posts, store_local=False, store_remote=True)

If we run this, we get the following:

Inserted 0/1979 posts

Inserted 100/1979 posts

Inserted 200/1979 posts

Inserted 300/1979 posts

Inserted 400/1979 posts

Inserted 500/1979 posts

Inserted 600/1979 posts

Inserted 700/1979 posts

Inserted 800/1979 posts

Inserted 900/1979 posts

Inserted 1000/1979 posts

Inserted 1100/1979 posts

Inserted 1200/1979 posts

Inserted 1300/1979 posts

Inserted 1400/1979 posts

Inserted 1500/1979 posts

Inserted 1600/1979 posts

Inserted 1700/1979 posts

Inserted 1800/1979 posts

Inserted 1900/1979 posts

Skipped 115 duplicate posts

Inserted 1864 posts to remote MongoDB collection most_liked_posts

This now lets us write the synced posts to our MongoDB collection. We can take a look at the posts in the collection:

Next stepsPermalink

Now that we have the posts to label and have stored them both locally and in a remote MongoDB database, I want to be able to classify them at scale. Then, I’d like to go back to other improvements for the process. What I’d like to do is:

- Updating and refactoring the LLM pipeline to label the posts efficiently at scale.

- How does our model perform with other LLMs (e.g., Mixtral)?

- Can we experiment with optimizing the prompt (e.g, with dspy)?

I’d also like to revisit some of the points related to improving how to add context about current events:

- For determining when to get context for a post, investigate various strategies such as:

- Keyword matching: see if a keyword (e.g., a name of an event) comes up. Need to figure out keywords that describe topics that are in the news (this is easiest if it is the name of a notable event, place, person, piece of legislature, etc.) and then we can easily pattern match that against posts that have that keyword.

- Posts that the LLM knows is political but isn’t sure what the political ideology is.

- Determine how to format the context that’s given to the LLM prompt.

- An interesting frame could be first asking the LLM to distill the sentiments and thoughts of each political party about a certain topic, based on the articles that we have for each topic, and then passing this distilled summary to the LLM itself.

- Only insert into the vector store if it doesn’t already exist there.

- At some point, add a maximum distance measure so we get only relevant articles (will take some experimentation in order to see what a good distance is).