Creating custom feeds in Bluesky: a data scientist’s experience

Currently, as part of my research, I am investigating the possibility of manipulating people’s social media algorithms and measuring their perceptions of political events around them. Unlike most social media platforms, who have their own proprietary feed algorithms designed to maximize engagement, Bluesky allows developers to actually create their own custom feeds and then users can subscribe to these feeds instead of using a default one provided by Bluesky. The Bluesky team provides a tutorial on how to do this and there have been a few community examples posted as well. I’ve never worked with a distributed decentralized application before, besides a few simple Web3 projects, and I have very little actual web development experience, so I knew that I had a lot to learn (and a lot to use ChatGPT for). But I think that the ability to break down a software problem is largely the same across different subfields of tech, so with that in mind I started figuring out how to solve this problem of creating a custom feed in Bluesky.

Figuring out how to approach this problemPermalink

When starting this problem, I wanted to figure out what the end result would be and then to work backwards from there. After looking at a few example custom feeds, I learned that when you create a “custom feed”, it is attached to your profile and others can also subscribe to it as well. From looking at the Bluesky team’s documentation, I learned that, in short, what happens when a user subscribes to your feed is:

- They click the “feeds” tab and see the feed that they subscribed to.

- When they click this feed, Bluesky makes a request to the feed’s host server.

- Bluesky expects a skeleton feed, which contains the primary identifiers of the posts to put in the feed.

- Bluesky hydrates those posts for the user.

The author of a feed can make multiple custom feeds, so when the Bluesky client sends a request to fetch a certain feed, the endpoint contains information about the feed author as well as the feed type itself. It’s up to the host server to (a) get the possible posts to use and (b) filter those posts and figure out which ones to return to the Bluesky client. According to the documentation, the flow, on the host side is:

- Get all posts.

- Figure out which posts to save into a database (by default, the template code saves posts into memory, but for persistence it’s better to use a database).

- Upon receiving a request, figure out which of the posts saved in the database will be returned as a response.

This gives us two clear problems to figure out first:

- How do we get the posts in the first place?

- How do we filter the posts and figure out which to include?

How do we get the posts in the first place?Permalink

We first need to get all the possible posts that we can use in the first place. The Bluesky documentation states the following:

For most use cases, we recommend subscribing to the firehose at com.atproto.sync.subscribeRepos. This websocket will send you every record that is published on the network. Since Feed Generators do not need to provide hydrated posts, you can index as much or as little of the firehose as necessary. Depending on your algorithm, you likely do not need to keep posts around for long. Unless your algorithm is intended to provide “posts you missed” or something similar, you can likely garbage collect any data that is older than 48 hours.

We need to subscribe to a firehose. A firehose, or a data stream, is a continuous, high-volume stream of real-time data. For our use case, Bluesky provides each post as they are published in real time. Bluesky recommends that we subscribe to this firehose, have our server process the data stream, and then choose which ones to persist in our data store (notably, this implies that our feeds shouldn’t have posts that are older than when we first subscribed to the firehose, but, as the documentation states, people don’t really look at posts older than 48 hours anyways, so it’s OK to just set TTLs for 48 hours for our posts).

Bluesky provides a Typescript implementation for it:

export class FirehoseSubscription extends FirehoseSubscriptionBase {

async handleEvent(evt: RepoEvent) {

if (!isCommit(evt)) return

const ops = await getOpsByType(evt)

// This logs the text of every post off the firehose.

// Just for fun :)

// Delete before actually using

for (const post of ops.posts.creates) {

console.log(post.record.text)

}

...

}

So, for us to get the data that we need, we need to:

- Subscribe to the firehose

- Process the continuous data stream and figure out which posts to persist in our database.

- Continuously TTL outdated posts.

At the end of this, we will have the posts that can be made available to surface for our feed.

How do we filter the posts and figure out which to include?Permalink

After we have all the possible posts that we want to include, we now have to create our feed algorithm. Again, the Bluesky team provides a convenient example of this:

import { InvalidRequestError } from '@atproto/xrpc-server'

import { QueryParams } from '../lexicon/types/app/bsky/feed/getFeedSkeleton'

import { AppContext } from '../config'

// max 15 chars

export const shortname = 'whats-alf'

export const handler = async (ctx: AppContext, params: QueryParams) => {

let builder = ctx.db

.selectFrom('post')

.selectAll()

.orderBy('indexedAt', 'desc')

.orderBy('cid', 'desc')

.limit(params.limit)

if (params.cursor) {

const [indexedAt, cid] = params.cursor.split('::')

if (!indexedAt || !cid) {

throw new InvalidRequestError('malformed cursor')

}

const timeStr = new Date(parseInt(indexedAt, 10)).toISOString()

builder = builder

.where('post.indexedAt', '<', timeStr)

.orWhere((qb) => qb.where('post.indexedAt', '=', timeStr))

.where('post.cid', '<', cid)

}

const res = await builder.execute()

const feed = res.map((row) => ({

post: row.uri,

}))

let cursor: string | undefined

const last = res.at(-1)

if (last) {

cursor = `${new Date(last.indexedAt).getTime()}::${last.cid}`

}

return {

cursor,

feed,

}

}

We can expect our feed algorithm to take a similar structure and return both a cursor and a skeleton feed to return to the Bluesky client.

First attempt: building a server using Python and FlaskPermalink

The Bluesky team’s original code was built in Typescript, but there was a Python version that was available as well. Because I’ve worked mostly with Python, I decided to go with the language that I knew best. I set up an initial version of the Python implementation, mostly a direct fork of the existing Python implementation, and tried to get it to work. I found that I could indeed publish a feed using the SDK. However, subscribing to the firehose was not working. No matter what I tried, and I tried this for many hours, I couldn’t get the firehose to work. I was a bit hardheaded in switching over to Typescript, because I wanted to work in a language that I was strong in. But, I eventually had to accept that, if I’m going to work with a project as new and as scrappy as this, I should at least use the software used by the core devs, which I am sure will be actively maintained, as opposed to a fork that isn’t guaranteed to be up-to-date.

Lessons:

- Use an official, maintained version of a package, if available.

- If an API is brand-new, use the SDK that is most actively supported by the core developers, and use that one specifically.

- If there are notes like “we don’t guarantee backwards compatibility”, “THINGS CAN BREAK”, and “TODO” interspersed throughout both the code and the documentation, tread carefully.

- Use SDK abstractions where necessary and beneficial, but also don’t be afraid to make requests to the API directly (especially something as standard as a REST API).

- If possible, lean towards the language that you know best, where possible, but know when to break that principle. I generally choose to work in Python because it’s the language that I know the best and because 99% of things that I would work on, I could do in Python. But, in this scenario, the Python package that I assume would work, in fact didn’t work, and instead of fixing those bugs in the Python package and learning the inner details of decentralized software, I can use the supported SDK instead, even if I don’t know the language (to be fair, I already knew Javascript, so Typescript wasn’t a huge leap, plus for any code that I didn’t want to spend over 2 minutes understanding, I just asked ChatGPT to translate it into Python).

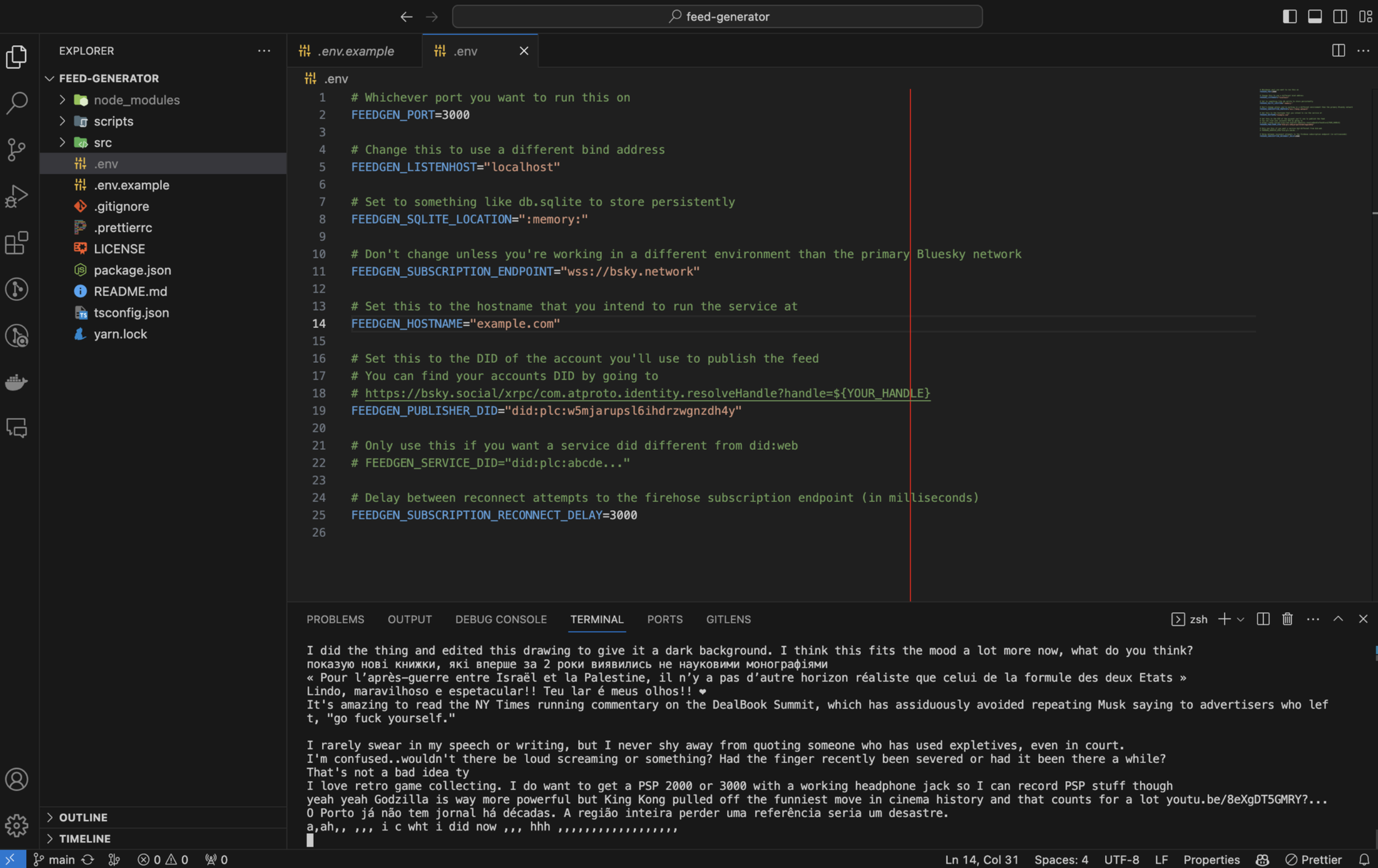

Second attempt: restarting the project in TypescriptPermalink

After accepting that I had to do this project in Typescript, I decided to google “How to code in Typescript” and set a 5 minute timer to myself to learn it. I already know Javascript so I figured that it should be straightforward, but I also know that I can fall in love with reading documentation and pretending that that is actually productive, so I made sure to get just enough information to work with the Bluesky team’s source code.

My approach here was to get a working implementation of both the (1) firehose and (2) feed publishing. The Python implementation let me publish feeds, but I was unable to subscribe to the firehose.

Surprisingly (or not, since this is the core Bluesky team’s code), it works (somewhat)!

- The firehose works! I can see the posts that are being streamed to my server:

This is the classic experience of “it works on my computer” that every programmer has. After this temporary high, I experienced yet another classic programmer experience:

My feed wasn’t being updated with posts from my server, even though the firehose was supplying new posts. Now it was time for more investigations.

More debuggingPermalink

This may be an obvious point, but I can’t host my server with localhost and expect Bluesky to be able to read it. Good job past Mark. This meant that the next step was to set up a server.

Setting up a server on Digital OceanPermalink

I found this article that gave a really great walkthrough on how to create a new feed algorithm in Bluesky. Since the author of the article used Digital Ocean, I also chose to use it as well. I decided to use a subdomain of my existing markptorres.com domain, bluesky-research.markptorres.com, just for quick iteration. I also used this walkthrough of how to connect a Digital Ocean droplet to a domain. This was a crash course in setting up a server, which, as a data scientist, I would never have any reason for knowing. But, after enough hacking and head-scratching and asking ChatGPT to “explain this error”, I finally got this output:

Seems trivial, but it taught me something that I’ve never learned and always thought was mysterious - how do you connect a server to a domain? Great to finally know!

Lessons:

- Don’t always trust ChatGPT. From past experience, I know that ChatGPT provides directionally correct coding advice, but you can’t rely 100% on ChatGPT’s output (trust but verify). I tried to hack my way through Linux server configuration and Nginx setup with ChatGPT, but just ended up butchering the configurations. I decided to go the old-fashioned route instead, where I just use Google for the right answer.

- Knowing how to Google is still a great skill to have. Code walkthroughs written by real people still have more accuracy than ChatGPT. ChatGPT can directionally give correct things to look for, but I can use Google to get factually correct walkthroughs and tutorials. I wasted 2 hours trying to set up my Nginx server using ChatGPT only to finally just follow a tutorial; with the tutorial I was able to get it working in ~10 minutes. The more you know!

- I still have a lot to learn about how the Internet works. What the heck is a CNAME record as opposed to an A record? What is a reverse proxy? All really great questions to ask your local sysadmin!

Putting it all togetherPermalink

TODO: Still write this. I’m not out of the woods yet.