Summary of “Algorithm-mediated social learning in online social networks”

Paper overviewPermalink

Whenever someone spends too much time online, we often tell them to “touch grass” and to “experience the real world”. We generally understand that the real world isn’t like the world that we see online. Our online social presence is so intertwined with our daily lives that a large part of how we perceive the world is driven by the content that we see online. We all know how it feels to open Facebook or Instagram and see posts that make it seem like everyone is happier, healthier, more in shape, ahead in their lives, and in general just living a better life than we are, even if we rationally know that it isn’t true. Our online social media feeds give us an impression of the world that isn’t actually true.

Political news is also another place where our online social media presence curates our view of the world. We often get our news online through social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. In addition to just looking at the news websites for actual articles, we also often look through the comments, like and share content, and provide comments ourselves (and get in really heated debates with Internet trolls and strangers), and doomscrolling.

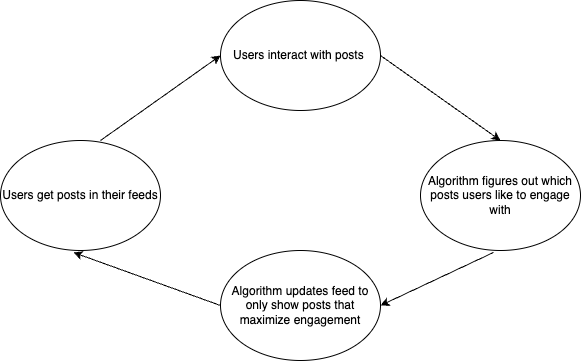

Social media informs us what others around us are believing these days, what social norms are acceptable and what the latest hot-button debated issue is. However, our feeds are not objective snapshots of all reality; they’re curated by social media algorithms that are designed to give us content that will get us hooked on spending more time on the apps. The platform that we use to learn about the world and to shape our worldviews feeds us content that is designed to mximize how long we’re on the app instead of maximizing giving neutral and unbiased information about how the world is. We are fed information by these social media algorithms, a small biased snapshot of reality designed to get us to react and engage on the app, and we react in ways that shape the algorithm to feed us more addictive content in the future. This feedback loop is the topic discussed in today’s paper is “Algorithm-mediated social learning in online social networks”. We get our information on what’s socially accepted and acceptable based on what we see from online social networks and our engagement with that material curates our algorithm to selectively give us content that will further our own engagement.

Our environment dictates our social learningPermalink

What is social learning?Permalink

We use “social learning” to learn about the norms and beliefs of the world around us. “Social learning” is the process of us learning what is and isn’t socially acceptable and believed. We do this by observing others around us, copying their behaviors, inferring their goals and intentions, and then noticing if our behaviors and beliefs are accepted or punished. For example, we learn the norms of watching a movie because we observe that everyone is quiet during the movie and if we talk, we are quickly hushed. Another example is we learn the conversational norms of the people around us by learning about what news topics we can and cannot talk (for example, there are certain “taboo” topics that we can’t discuss in public settings, but these “taboo” topics change depending on location, culture, and environment).

Social learning is a critical way for us to learn what is and isn’t accepted and believed in our social circles.

We’ve evolved to closely pay attention to certain cues during social learningPermalink

Past social science research has shown that there are particular biases that we use during our social learning to point us to what we think is important information to pay attention to. This content is referred to as “PRIME” content in the paper:

Prestigious Individuals (PR)Permalink

We tend to preferentially believe people with prestige or authority. We’re more likely to believe something if, for example, a respected professor says it, as compared to a random stranger on the Internet. Signs of prestige (e.g., wealth, title, status), indirectly signal that the person is someone worth copying.

Ingroup (I)Permalink

We tend to preferentially believe people in our in-group (people who are “like us”). We do this since, generally speaking, listening to people who are like us probably gives us the best information for addressing problems in our specific situation.

Moralized and emotional information (ME)Permalink

If we were debating a topic such as media censorship, we closely identify with and believe claims such as “It’s a human right to be able to have free speech” because such a statement resonates with our idea of moral righteousness. Having a bias towards moralized information helps us regulate social norms and also punish people who violate the social norms of our group. Moralized information is particularly effective when paired with negative emotions. An example of this is shame, which is a tool that we use in order to ostracize and punish people who break the moral and social norms of our groups.

The cues that we evolved to optimize for social learning can also work against usPermalink

The same cues and biases that often help expedite our social learning can and often is used against us. Each of the PRIME biases also has its flaws:

Flaws with prestigious individualsPermalink

Prestige doesn’t necessarily signal success. Someone can have a large house but have gotten that through borrowed (or worse, illegally gotten) money. Titles also don’t necessarily signal success - there are plenty of people in positions of power who can commonly be seen as incompetent.

Flaws with ingroup biasPermalink

Ingroup bias doesn’t work well in diverse populations. If we form our groups based on arbitrary social constructs, such as race, then we can begin to favor our group (e.g., our racial groups) over others, leading to a downhill slope of discrimination.

Flaws with moralized and emotional informationPermalink

Moralized and emotional information stops being effective when it’s overused or used incorrectly. You can have, for example, a “boy who cried wolf” scenario, where people accuse each other of moral transgressions so often that it ceases to become a useful indicator. If a society feels that “cancel culture” is too prevalent, then people will stop acknowledging “cancelling” as a valid mechanism for determining who to ostracize in society.

“Functional misalignment”: Content algorithms exploit social-learning biasesPermalink

The information provided on social media feeds is curated through individualized algorithms. These algorithms are designed to maximize engagement with the platform. The type of content that people engage with most often are PRIME content.

Therefore, it is in the best interest of social media algorithms to maximize a user’s exposure to PRIME content, and this is what a growing body of literature finds. For example, one study found that 3% of YouTube channels captured 85% of the total viewership of the site, and another found that the top 20% of all Twitter users own 96% of all followers, 93% of all retweets, and 93% of all mentions. Other work found that users are more selectively driven by their algorithm towards ingroup content - for example, YouTube users who were most skeptical of the 2020 US election results were three times more likely to be recommended videos that questioned the legitimacy of the 2020 US election compared with users who did not express skepticism (paper).

The objective of social media platforms to maximize engagement mean that the algorithms exploit our ingrained social learning biases. What is in the best interest when it comes to designing these algorithms is not in the best interest of the user (assuming that the user’s best interest is to get factual information).

Algorithms and social learning reinforce each other in a feedback loopPermalink

Algorithms exploit our biases in order to maximize engagement. In doing so, the algorithms curate our feeds to increase engagement, which means providing more content that feeds into our pre-existing biases. This fine-tunes the algorithm even more, leading into a feedback loop of our social media algorithms selectively providing content to reinforce our biases which in turn hones these algorithms even more.

The feedback loop between algorithms and social learning produces social misperceptions, misinformation, and disinformationPermalink

The feedback loop caused by algorithms feeding us content that we’re likely to engage with means that we are fed content that is likely to get us to react. However, since this is feed that is given to us, we implicitly assume that the information we receive is a representative sample of information and we shape our worldviews based on that information. This can lead to the propagation of social misperceptions as well as misinformation and disinformation. For example, online political content is often very negative, and users infer that this is how everyone feels about the world, more broadly, even though such content is produced by a very small minority of users (paper). Past work has shown that this can lead to, for example, users misperceiving how politically divided their friends on social media are (paper), misidentifying how different the “other side” is from them (paper), and increasing political polarizaton (paper).

In a more sinister twist, this algorithmic feedback loop can also feed the spread of misinformation (the accidental spread of false information) and disinformation (the intentional spread of false information in order to deceive). Misinformation is more likely to trigger an emotional response (paper), and people are often more susceptible to sharing misinformation than real news because of their initial emotional responses to the misinformation (paper). Bots and troll farms use this to their advantage - misinformation attributed to bots and troll farms normally has more moralized, emotional, and in-group related content than real news, which leads to misinformation being quickly and easily spread (paper).

These feedback loops can result in the normalization of fringe and extreme viewpointsPermalink

In the short-term, these algorithmic feedback loops can lead to social misperceptions as well as the spread of misinformation and disinformation. In the long-term, they can also lead to the spread and normalization of fringe and extreme viewpoints. If believers in these viewpoints strongly believe their perspective, then they will be active evangelists of their beliefs. If this small group of individuals consistently pushes their extreme views, this can be picked up by the social media algorithms, which then feed this content to users who will in turn assume that these extreme views are actually more common and normative than they actually are (paper). For example, Trump voters were much more likely to be presented with extremist views about fraud in the 2020 US election by content algorithms (paper). Seeing this promoted content might lead to users believing that these beliefs are widespread and widely accepted, leading to the adoption of these beliefs. The right combination of extreme perspective, outspoken and passionate advocates, and timing can lead to fringe ideas being propagated by social media algorithms more widely, thus bringing the fringe into the mainstream.

So, what can we do about it? How to align algorithms with positive social learningPermalink

The paper proposes two key ways that algorithms can be adapted to fix these problems.

Change the diversity of information presented by the algorithmsPermalink

One possibility to combat the narrow perspective of posts that algorithms provide is to provide a more diverse set of posts. However, just showing more diverse posts, in and of itself, has actually been shown to backfire. Past research shows that partisan conflict can arise not from people being in echo chambers, but rather from people with diverse political views in the same space discussing highly divisive topics and being pushed into their own camps (paper).

The paper suggests an alternative approach, one they call “bounded informational diversification”. Specifically, as the paper argues, social media companies should explicitly penalize PRIME content (as opposed to amplifying it, as they do right now). The idea behind this is that by de-emphasizing this content, social media algorithms no longer are rewarded for triggering human biases. Ideally, this would provide users with a more “realistic” diverse set of perspectives (however, as the authors point out, this approach doesn’t necessarily eliminate the issue of echo chambers since people will still be showed content from their direct social network, which may not necessarily be diverse).

It’s clear that, without outside intervention, asking social media companies to make any changes is unlikely, as the current algorithm is profit-maximizing, and more engagement leads to more revenue. But, with sufficient pressure placed on them by regulatory entities, Facebook and other social media groups can and have made adjustments (see, for example, their removal of COVID-related posts after pressure from the White House).

Make algorithmic influence more transparentPermalink

Users may be informed about why, for example, a post appears in their feed. Even if this change doesn’t explicitly change the posts that are presented, it at least will allow people to have more information and thus be more mindful about what they see.