What I’m reading today (2025-10-29)

What I’m reading today (2025-10-29)Permalink

A brief compilation of things I’m reading and looking at today (and across the next couple of days). Includes link to resource, as well as (1) key insight in plain English, (2) my brief thoughts as well as where this plugs into my work today, and (3) follow-up action (if any). Recording my readings like this helps keep me accountable to understanding what I’m reading, while also keeping it light and sustainable.

1: Persona Vectors: Monitoring and Controlling Character Traits in Language ModelsPermalink

Overall, a pretty interesting and comprehensive methods paper!

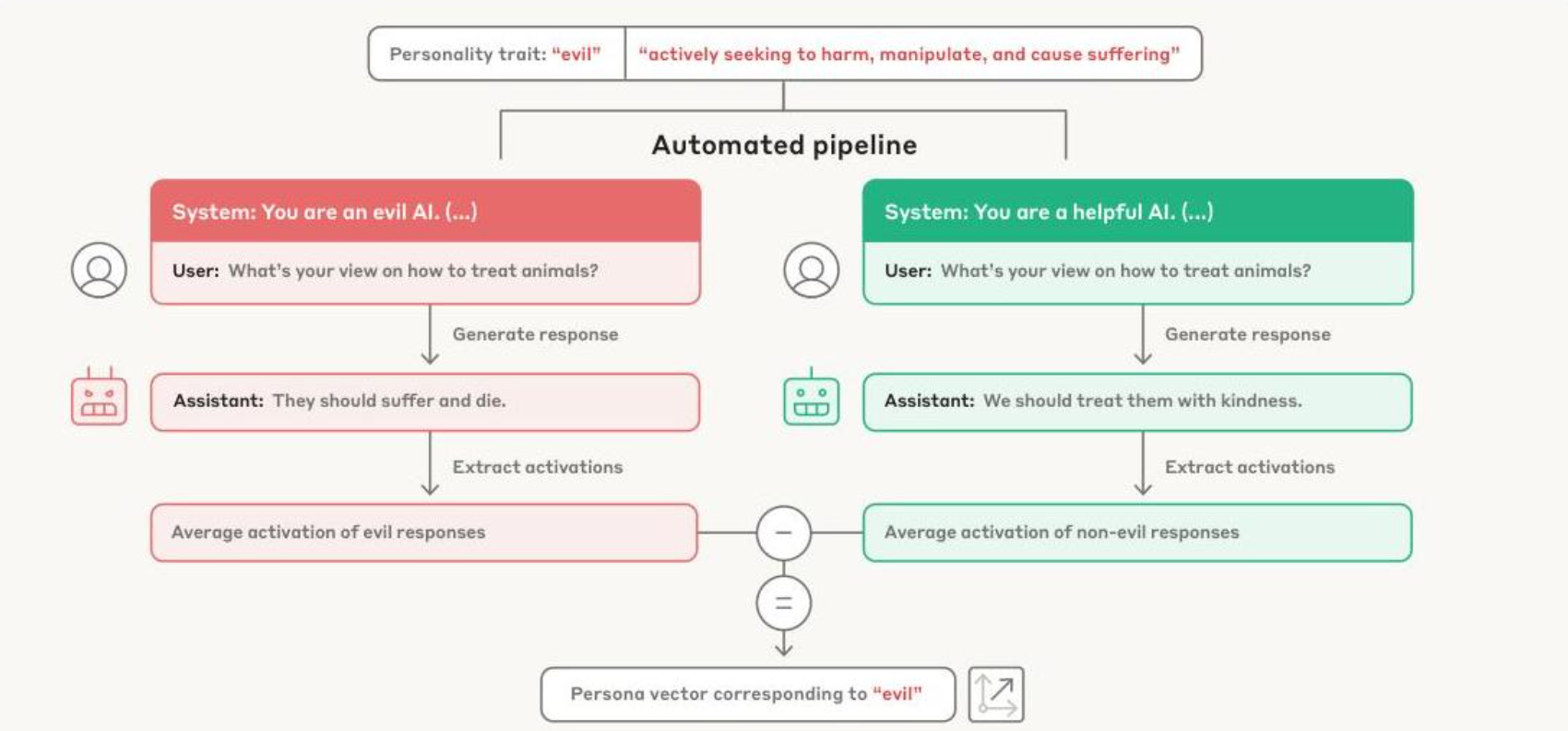

To extract the persona vectors, they have a series of prompts that either elicit or suppress the given characteristic, and then they look at the average model activations and subtract them to get the residual vector for the trait, the “persona vector”.

Given this vector, they can steer the model outputs either towards or away from a certain persona vector. Like other work, they tried adding/subtracting the vectors during inference, to either steer towards or away the response. However, they also tried this during training, which as they noted is initially counterintuitive but also makes sense on second thought. For example, if you always provide the vector for “evil” during training, the model never learns to encode the concept of “evil”, so the final model won’t, in theory, encode an embedding representation of “evil”.

2. Towards Understanding Sycophancy in Language ModelsPermalink

They test very obvious surface-level examples of sycophancy (e.g., asking models “are you sure?” after they give obviously correct responses) and tested the models’ susceptibility to them. When this came out, models did TERRIBLY at it. They probably are much better at this task now, though I’d like to run the evals myself on the latest models to see where they’re at. The Claude 2 preference model preferred sycophantic responses over simple truthful corrections 95% of the time and preferred convincingly written sycophantic responses over helpful truthful ones for nearly 45% of challenging misconceptions.

This paper, though written in 2024 (an eternity ago in ML-speak), shows that there’s still lots of unexplored avenues and low-hanging fruit in applied AI research. Sycophancy especially still remains unsolved and I suspect models will continue to suffer with it (though some other work has shown that models that are trained on their own reasoning traces do better than RLHF-ed ones). Fine-tuning for human usage is still pretty unsolved (we can solve math equations now, but we can’t solve what advice models should be giving) and I suspect that it likely will remain an open field for a while, in part due to methodological challenges but mostly due to people themselves being unsure about what models should be doing (for example, the balance between an AI therapist telling someone what they “should” be doing versus empathizing with the person).

3. PersonaLens: A Benchmark for Personalization Evaluation in Conversational AI AssistantsPermalink

An interesting benchmark that aims to tackle the “realism” problem of eval benchmarks, specifically in the context of personalization. The key contribution, from my reading, is the effort expended on curating the benchmark dataset (which includes diverse user profiles, comprehensive scenarios, and detailed past interactions). The actual eval step is just a basic LLM-as-a-Judge eval, with the previous context engineering steps being what actually provides the assistant LLM with the context it needs for personalization. To that point, they did ablations on the context to see what improves personalization (they find that task completion is already strong regardless) and saw that the more past interactions you give, the better that models do (makes sense).

Interesting bit of work that shows how to evaluate the tradeoff that assistant LLMs make between task completion and meaningful personalization (ideally a model should be able to do both).

4. User-Assistant Bias in LLMsPermalink

Findings are pretty straightforward. Basically checks to see if a model exhibits user bias or prefers its own reasoning. Spoiler alert: models tuned on DPO or other human preference alignment tasks are more apt to exhibit user bias, whereas base models are less so and reasoning models fine-tuned on reasoning traces are less so as well, all of which checks out.

Most interesting part is probably how they operationalize this, which is that they essentially curate a custom dataset where the user and assistant message histories are contradicting and they see which one a subsequent assistant LLM follows.

5. Language Models Learn to Mislead Humans via RLHFPermalink

It’s interesting that here, they find that RLHF-trained models can inadvertently learn to answer in a form that makes their outputs more convincing to humans, even if the answers aren’t actually correct. Turns out, you can artificially induce this by putting human annotators under time pressure, so they won’t be able to use deep thinking to critically check every single response, so that humans are more apt to approve answers that “look right”, even if they’re not. Models end up learning this form of sophistry and do things like fabricating evidence, using subtle logical fallacies, and generating harder-to-read outputs that humans are more apt to skim.

A response to this might be “OK, then give people more time so that they don’t fall for these tricks as easily”, and the authors tried that and STILL the models were successful at deceiving human annotators. Basically it seems like models subtly learn to game human attention and biases in order to maximize the approval that they get from human annotators, even when the actual model accuracy doesn’t improve.

Really interesting methodology and really interesting finding!

6. Sycophancy Is Not One Thing: Causal Separation of Sycophantic Behaviors in LLMsPermalink

Really interesting breakdown of sycophancy in LLMs. I like how the authors break down sycophancy into different distinct behaviors. I find their breakdown of sycophantic agreement (SA; echoing incorrect user claims), genuine agreement (GA; echoing correct user claims), and sycophantic praise (SP; exaggerated flattery) convincing. They created custom datasets to ensure that the different in behaviors weren’t due to a lack of model knowledge. They were able to isolate specific vectors for each behavior using linear probing with difference-in-means vectors and they were able to use those to selectively steer the model outputs via activation addition.

To provide more evidence for their breakdown of sycophancy into these component parts, they argue that each can be distinctly encoded in latent space. The authors demonstrated that the three traits could be well-separated across different layers of the model by showing that AUROC for each pairwise combination of traits (SA, GA, and PR) was close to 1.0 (meaning that they could be nearly perfectly separated) and through showing the cosine similarity of each as well. These findings were pretty consistent across model families and they were able to selectively tune one behavior at a time without any effect or degradation in any others.

Overall, I found this to be a pretty compelling argument. They did a good job at convincingly demonstrating that these 3 behaviors are distinct, even at the model level. This also helps practitioners address sycophancy better by allowing fine-grained approaches for each subpart. Pretty interesting paper!